“The only cure for these overlapping ills is an injection of political resolve”—

Pramila Patten, UN Special Representative on Sexual Violence in Conflict

Introduction

War and displacement have a devastating toll on societies with women and children disproportionately bearing the brunt of these crises. While sexual violence remains a criticalfor concern, the impact extends far beyond, including economic deprivation, exclusion from community participation, and systemic marginalization. While, the international community has attempted to address these challenges through frameworks such as the Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) agenda, significant gaps remain in implementation and enforcement.Given these gaps, it is crucial to explore the multifaceted consequences of hardships, social integration, and long-term resilience-building efforts that transcend national and cultural boundaries. This examination sheds light on how societies confront adversity, adapt through collective action, and build enduring frameworks for inclusive and sustainable recovery.

The Structural Vulnerabilities of Women and Children in Conflict

Gendered Disparities in Pre-Conflict Societies

Across multiple regions, women enter conflict situations already deeply entrenched in pre-existing structural inequalities. Socioeconomic disparities, limited access to education, and systemic gender discrimination (often justified under the guise of religion/culture) exacerbate their vulnerability in times of war. In the Occupied Palestinian Territory, only 19% of women participated in the formal labour force prior to the outbreak of conflict, a statistic mirrored in Yemen and Iraq. In the absence of this financial independence, displaced women become particularly susceptible to exploitation when they are separated from their communities as a whole. Recognizing and addressing these structural disparities is therefore essential to building any sustainable post-conflict framework that does not replicate cycles of dependency and marginalization.

Escalation of Gender-Based Violence

Sexual violence in conflict settings is frequently weaponized as a means of asserting control over populations. Reports of systematic rape in Ethiopia’s Tigray region and the resurgence of military leaders with histories of sexual violence in Myanmar’s Rakhine state highlight the continued use of gender-based crimes as instruments of war. In Afghanistan, the exploitation of boys through the practice of bacha bazi is a stark reminder that gender-based violence extends far beyond women alone, profoundly affecting other vulnerable groups as well.

These atrocities persist due to weak accountability mechanisms.. Survivors face insurmountable barriers in seeking justice from local remedies, while global ones often remain inaccessible, particularly where perpetrators continue to retain power. The persistence of such violence, coupled with systemic impunity, reveals how gender-based crimes are not only consequences of war but also instruments that shape its very dynamics. Addressing them thus becomes central to any conversation about justice, reconciliation, and durable peace.

The Economic Ramifications

Loss of Livelihoods and Financial Independence

Conflict-induced economic collapse disproportionately affects women, especially those who suddenly become heads of households due to the deaths or disappearances of male family members. In Yemen, where 30% of displaced households are female-led, restrictive legal and financial barriers prevent women from accessing employment and social services. Circumstances have, therefore, forced many of them to turn to informal labour markets, rife with exploitative conditions and extreme wage disparities.

However, women-led economic reintegration initiatives have been instrumental in mitigating these effects. In Ethiopia, local savings groups provide interest-free loans to women, a luxury that institutional structures fail to provide, enabling them to rebuild their livelihoods in the aftermath of conflict. However, such grassroots efforts do not receive enough financial aid through formal governance structures. This emphasizes the need for governments and international organizations to direct the same towards suitably flexible gender-responsive economic policies in real time.

The Burden of Unpaid Work

The economic exclusion of women in war zones is exacerbated by the increased burden of unpaid domestic labour. Women in displaced communities are often responsible for securing food, water, and medical care under extreme conditions. In South Sudan, a country demolished through civil war, over 90% of refugee women perform caregiving roles, while many are forced to withdraw from economic participation (even informal) entirely. This exclusion not only deepens cycles of poverty but also diminishes women’s agency, leaving them more vulnerable to exploitation, domestic abuse, and social marginalization, from which they already disproportionately suffer.

Economic independence becomes crucial to enable women to rebuild their lives, support their families, and contribute to post-war recovery efforts. The absence of women in economic structures weakens community resilience, since financial security forms the foundation of post-conflict stability. When women have access to economic opportunities, communities are better able to secure healthcare, education, and legal protections, fostering lasting recovery and social cohesion. Economic empowerment, therefore, is not peripheral but foundational to recovery. Integrating women into economic structures transforms them from passive recipients of aid into active architects of reconstruction, aligning directly with the broader goal of inclusive and resilient post-conflict societies.

The Social and Political Exclusion

Barriers to Social Integration

Displaced women frequently face social stigmatization, particularly when they are perceived as having associations with armed groups. In post-ISIS Iraq, thousands of women have been denied identification documents due to their alleged ties to ISIS members, rendering them stateless and unable to access healthcare, education, or employment. Similarly, in Myanmar, the Rohingya crisis has left hundreds of thousands of women and children in a legal limbo, with host countries reluctant to grant them permanent status. Moreover, deportation, long accepted as a sovereign prerogative, is now increasingly occurring in a legal void, where administrative justifications take precedence over fundamental human rights, with no single global framework exclusively governing deportation standards and protocols.

Missing Mentions: Underrepresentation in Decision-Making

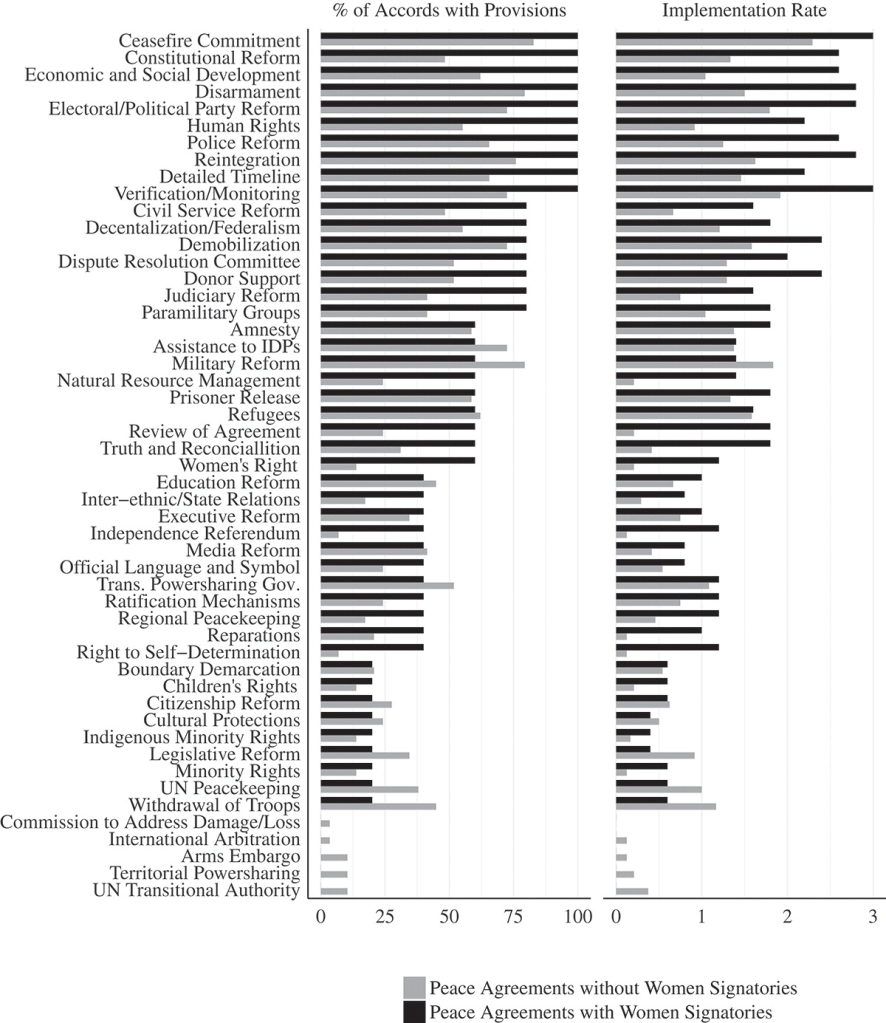

UN Security Council Resolution 1325, underscored the necessity of including women in all stages of conflict resolution, yet their representation remains strikingly low. Empirical studies demonstrate that peace agreements with female representation are more likely to last longer. Despite this, women constituted only 9.6% of negotiators in major peace agreements in 2023.

Between 1990 and 2016, less than 11% ceasefire agreements contained gender provisions, reflecting a systemic exclusion at the early stages of peace processes itself. The Nepali peace process, despite its 12 ceasefire agreements, never mentioned women, successfully exemplifying this disparity. This oversight is critical, as ceasefires and pre-negotiation frameworks set the agenda for post-conflict reforms, often limiting the scope of further negotiations. Evidence suggests that post-conflict settings can drive gender reforms as well, subject to conducive environments. For instance, African nations emerging from war showing higher female legislative representation and faster adoption of women’s rights than stable counterparts.

Gender-related commitments often go unimplemented or are poorly enforced unless reinforced by political power-sharing frameworks that enhance both inclusivity and accountability, as evidenced by the Data from the Peace Accords Matrix. This marginalization further cements the need for institutional mechanisms to strengthen women’s representation in post-conflict governance. Such mechanisms can follow the example of Colombia’s 2016 peace accord which integrated gender quotas to boost female participation in reconstruction efforts. For peace to be truly sustainable, women must be actively involved at all stages of negotiation and not be treated as an after-thought, demonstrated by the graph below.

Fig 1. Women’s Participation in Peace Negotiations and the Durability of Peace

Health and Education: The Overlooked Crisis

Disruptions in Maternal and Child Healthcare

In 2023, 1,521 attacks on healthcare facilities across 19 conflict-affected countries resulted in over 2,000 casualties, depriving millions, particularly women, of critical medical services. In Haiti, Mali, Myanmar, Sudan, Ukraine, and the State of Palestine, targeted assaults on health centres severely restricted access to life-saving care, including essential sexual and reproductive health services, further exacerbating the already dire humanitarian crisis.

Calls for international responses have been, to say the least, unsatisfactory. Even actions by powerful nations such as France’s renewing voluntary contributions to the ICC Trust Fund for Victims, remain isolated and insufficient. The failure to integrate reproductive healthcare into humanitarian responses further compounds these issues, leaving pregnant women in war zones without essential medical care.

Educational Disruptions and Child Exploitation

The destruction of schools and the militarization of educational spaces have pushed millions out of formal education systems with gender-based targeted attacks. The recruitment of child soldiers remains a grave concern in Sudan, where displaced youth are particularly vulnerable to exploitation by armed groups. In Pakistan and Afghanistan, oppressive regimes have targeted educational institutions with bombings. In parallel, sexual violence has been committed against girls and women in Camerron, Colombia, South Sudan.

Programs such as the Educate a Child Initiative in Jordan have provided alternative schooling for refugee children, demonstrating the viability of flexible education models in conflict settings. However, these initiatives require sustained funding and broader inter-governmental cooperation to be scalable across multiple war-affected regions and maintained for prolonged periods.

Rebuilding Lives: The Post-Conflict Recovery

Women as Architects of Innovative Stability

Women are central to post-conflict reconstruction, yet their contributions are often overlooked. In South Sudan, female-led peace networks have mediated local disputes, helping curb further displacement, while in Uganda, refugee women have formed agricultural cooperatives, fostering economic stability for displaced communities. These efforts underscore the need to formally integrate women into recovery programs rather than confining their role to peripheral humanitarian initiatives.

Strengthening Accountability for Sustainable Reintegration

Despite existing mechanisms like the International Criminal Court, the UN Special Representative on Sexual Violence in Conflict, and the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, weak enforcement enables ongoing impunity. Strengthening hybrid courts like the Special Criminal Court in the Central African Republic and embedding Women Protection Advisers within UN peacekeeping missions (both military and otherwise) are critical.

In addition to the specific policy outputs suggested throughout, long-term recovery must prioritize economic reintegration, modelled on Colombia’s Special Jurisdiction for Peace, rather than short-term aid alone. Inclusive gender-sensitive policies in peacekeeping and stricter prosecution of war crimes, with ramifications reverberating globally, remain key to achieving sustainable peace.

Conclusion

The multifaceted impacts of war and displacement on women and children underscore a critical reality: conflict exacerbates pre-existing structural inequalities, weaponizes gendered violence, undermines economic agency, and perpetuates political and social exclusion. This analysis has demonstrated that the consequences of war are not isolated but intersect across social, economic, and institutional domains, producing cumulative vulnerabilities that impede sustainable recovery.

At the same time, evidence from post-conflict contexts highlights the centrality of women as agents of reconstruction, through leadership in peace networks, economic initiatives, and community stabilization efforts. The persistence of gaps in implementation of frameworks illustrates that ceasefires or formal conflict resolutions alone are insufficient. Sustainable peace requires the systematic integration of gender-sensitive policies across governance, economic reintegration, education, and health sectors, accompanied by robust accountability mechanisms. A ceasefire without structural reform risks leaving women and children in a continued state of marginalization. Enduring peace and resilience are contingent upon inclusive approaches that position women at the core of decision-making, reconstruction, and post-conflict governance. Only through such comprehensive and sustained interventions can the cycle of gendered violence and systemic exclusion be effectively disrupted, paving the way for truly resilient and equitable post-conflict societies.

Leave a comment