After almost 17 years of attempting to regulate Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ARTs), India found some firm footing in the form of the Assisted Reproductive Technological (Regulation) Act and Surrogacy (Regulation) Act (“Surrogacy Act”) in 2021.

These legislations aim to regulate and supervise surrogacy and ART clinics, prevent misuse, and ensure safe and ethical practices, while also establishing a legal framework for children born through ART.

ARTs, as defined by the American Centre for Disease Control (CDC), are “any fertility-related treatments in which eggs or embryos are manipulated”. Surrogacy is also one of the forms of ARTs. Surrogacy refers to an arrangement where a person or a couple (intending party) decides to have a child through the womb of another woman. Surrogacy can be classified based on embryos and remuneration. On this basis of the latter, Surrogacy can be altruistic or commercial. Altruistic is solely based on the goodwill of the surrogate mother and does not include any kind of monetary compensation apart from medical expenses. While in the commercial form, certain monetary compensation is given to the surrogate mother, apart from the medical expenses. The Surrogacy Act puts a blanket ban on commercial surrogacy and only allows for the altruistic form.

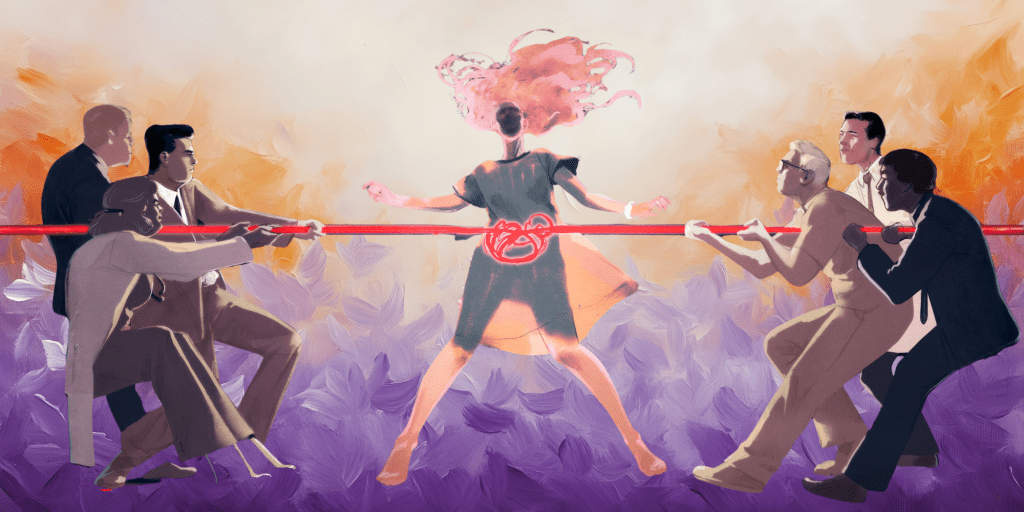

The legislative reasoning behind the same is to “prevent bodily exploitation of poor women”. However, what the legislature fails to understand is that banning the commercial form in its entirety only undervalues a woman’s labour and makes them more vulnerable to exploitation. While this adversely affects all the stakeholders, including the intending parties and their right to family, this essay examines the ban only from the perspective of surrogate mothers.

The essay, in its first part, encapsulates the extent of the surrogacy market in India and issues faced by it after the implementation of the surrogacy act. The second part, argues that a blanket ban on commercial surrogacy violates the bodily autonomy of surrogate mothers and their right to livelihood by denying them their rightful monetary compensation. Lastly, the author advocates the need for structured contracts and the facilitating role of the state over a complete ban.

The Surrogacy Market in India

The efforts for regulating Surrogacy began in 2005 when the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare came up with “National Guidelines for Accreditation, Supervision, and Regulation of ART in India”. It was not drafted to regulate surrogacy exclusively. Later, the case of Baby Manjhi Yamada v. UOI accepted the legal validity of surrogacy, thus opening many opportunities for the ART industry to thrive. It was only in 2016, due to the media coverage of surrogacy, especially the transnational form of it, that a public interest litigation was filed to ban commercial surrogacy. Hence, the regulation of surrogacy was separated from the ART bill and prioritized.

India, because of the absence of any robust regulatory framework and low cost became a “Surrogacy Hub”. There was an upsurge in Surrogacy clinics in India, especially in Anand – a remote town in Gujarat. In fact, in 2012, a study conducted by the UN revealed “the economic scale of the Indian Surrogacy Industry which came out to be 400 million dollars a year with more than 3000 fertility clinics all over the country.” In 2015, the surrogacy market in India was estimated to be more than 2.3 billion.

A follow-up study was conducted by the India Forum in 2019 when the Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill was being processed. The repulsive effects were already felt in Anand and Ahmedabad. A lot of surrogacy clinics had already begun to shut down. Many foreigners also stopped coming to India for surrogacy. Many potential surrogate mothers felt that they should be paid adequately if they were to take such risk of pregnancy.

After the implementation of the act, there has been an upsurge in the cost of surrogacy and black marketing has also led to more exploitation of surrogate mothers. The blanket ban not only adversely affects vulnerable stakeholders but also violates their constitutional rights.

Through Constitutional Lens: Right to Bodily Autonomy & Livelihood

As Nivedita Menon quotes in her book, “Motherhood is a biological fact and fatherhood is a socio-legal fiction”. Surrogacy challenges this traditional notion of motherhood. It has made it possible to separate different aspects of motherhood. Three Different women could potentially perform the key functions of a mother – “providing genetic material (the egg donor), gestating the fetus for nine months (the surrogate or gestational mother), and rearing and bringing up the Child” rather than all three functions being fused into one woman. Another interesting aspect of surrogacy is that it attaches an economic cost to pregnancy, which is otherwise considered to be a biological function and a moral duty.

This redefinition of motherhood not only challenges traditional roles but also raises important questions about a woman’s autonomy over her body and the economic value of reproductive labor.

In the context of surrogacy, the right to bodily autonomy facilitates the right to livelihood. Both rights are guaranteed by The Constitution of India (“Constitution”) through Article 21. The Supreme Court of India (“Supreme Court”) through Suchitra Srivastava, recognized a woman’s right to make reproductive choices (including procreation and abstaining from it) as a dimension of Article 21. Devika Biswas also recognized women’s autonomy and gender equality as core elements of women’s constitutionally protected reproductive rights. While the Court recognizes a woman’s right to continue or abort her pregnancy, the flawed understanding of the Surrogacy Act interferes with the surrogate mother’s right to decide on the conception of pregnancy because it does not allow them to carry a fetus for their financial interest.

The Surrogacy Act also violates the rights of surrogate mothers to practice their profession under Article 19(1)(g). The altruistic form of surrogacy essentially denies the status of “profession” to surrogacy which does the woman more harm than help. Denying basic legal recognition to their work, deprives them of benefits of employment and makes them soft targets for exploitation.

Hence, this understanding of surrogacy naturally affects their right to livelihood as well because the legislature expects women to go through the physical and mental toll of pregnancy solely out of compassion. This reflects the underlying heteropatriarchal tone of the legislation which undervalues the woman’s labour by labeling it as a natural duty or an act of goodwill.

By restricting a woman’s ability to make autonomous reproductive choices, the Surrogacy Act not only infringes on bodily autonomy and livelihood but also fails to meet constitutional standards of justice and fairness.

From a constitutional perspective, this act fails the “just, reasonable, and fair” test as laid down in Maneka Gandhi v Union of India . The surrogacy act miserably fails to achieve its objective of “preventing the exploitation of women”, it in turn, plans to tackle commercial surrogacy by depriving a woman of her rightful income rather than recognizing and regulating the profit-driven and private healthcare sector of ARTs.

Recommendation

As it can be concluded from the above discussions, Surrogacy is an extremely complex issue involving multiple stakeholders and their rights. Practically, finding “relatives” who are willing to be surrogates for the intended party is close to impossible due to the stigma associated with surrogacy. There is no basis for classification between altruistic and commercial surrogacy and the only visible intention of the legislature is to scrap the economic value attached to a woman’s reproductive labor.

Secondly, expecting women to go through the extremely traumatic and draining experience of pregnancy without any monetary compensation is unreasonable and clearly driven by patriarchal assumptions. The legislative motive rather than regulatory seems more of a moralistic intervention. Many scholars reject the concept of commercial surrogacy on the grounds of “public policy”. However, it is important to understand that the society’s perception of morality dictates public policy. Today’s society is largely inspired by patriarchy, caste hierarchy, and economic inequalities. Commercial surrogacy would remain a practical reality even if we accept the public policy argument. For example, India banned the option of surrogacy for gay couples in 2012, many clinics started moving the surrogate mothers to neighbouring countries such as Nepal which exposed the innocent surrogates to even greater risk.

Many countries like Russia and Israel and States like California have found a middle path through “Surrogacy Contracts” where all the stakeholders are legally regulated. California is known as the “Surrogacy friendly” state because it opens the option of surrogacy for single parents and homosexuals again.

The Surrogacy Act also fails to see the surrogates in the fused roles of caregivers, workers, care-receivers as well as epistemic and moral agents. The surrogates need proper medical care during and after pregnancy. A recent study by SAMA found that 2 out of 9 surrogates had a postpartum hysterectomy. Structured contracts would extend the benefits and protection like Insurance, Medical Treatment and a stable income to the vulnerable surrogates.

Secondly, surrogacy also gives rise to a lot of complex issues which need a proper redressal mechanism and awareness programmes especially for the potential surrogate mothers which would enable them to take care of their physical, mental and economic interests.

Leave a comment