Introduction

In an industry where power often eclipses the truth, can a single woman’s unembellished voice pierce through this veil without being silenced or distorted? Released in 2023, Anand Ekarshi’s National award-winning “Aattam” follows Anjali, the lone female performer of a theatre troupe who accuses a fellow actor of molesting her. Her fellow co-stars term her claims to be tactile hallucinations– in effect protecting the accused by weaponizing morality.

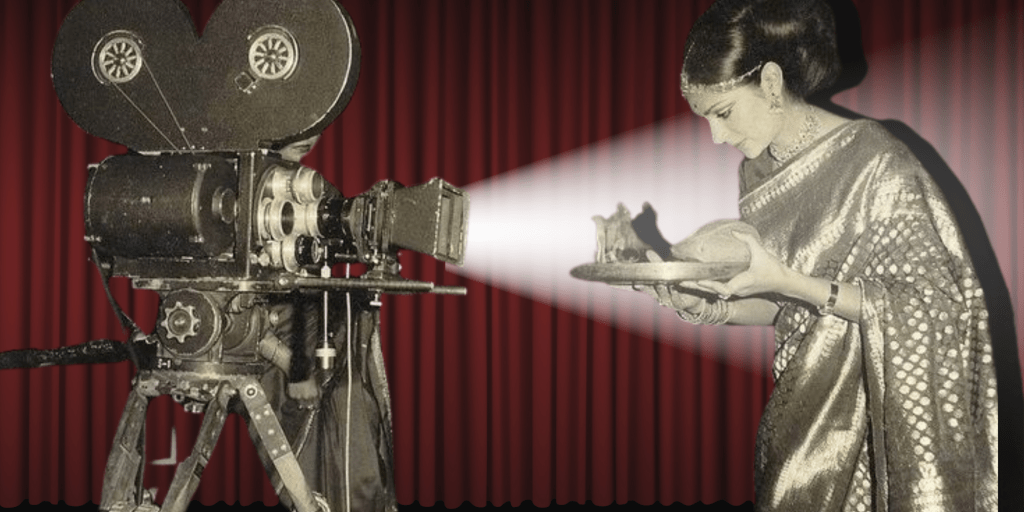

Considering the fading impact of the #MeToo movement and more specifically, incidents like the abduction and sexual assault of a prominent Malayali actress by Dileep, a key figure in the Malayalam film industry, “Aattam” can be seen as a haunting reflection of the unmistakable pattern of complicity and denial within the Indian film industry and its consequent inertia.

These are not just isolated episodes, but symptomatic of the industry as a whole. The Dileep case served as a catalyst in the commissioning of the Justice Hema Committee in 2017 by the Kerala government. The committee laid bare the vulnerabilities within Mollywood in its 2019 Report, but the same is mirrored across Bollywood and its regional limbs, from unstructured contracts and a lack of internal complaint mechanisms, all the way to a culture that expects women to continually “compromise” and “adjust”– innuendoes for sexual favors. The report’s critical findings remain largely unimplemented, revealing the reluctance – or perhaps disinterest – of the authorities and industry stalwarts to act decisively against powerful perpetrators. How many more women must endure humiliation and violation before the industry admits to its complicity? How long will these power structures continue to shield the perpetrators? Why is justice still a facade in the light of stringent laws, and can an industry famed for storytelling ever rewrite its own narrative?

The report was shelved for almost 7 years, before being released for the public in 2024. Running a fine-toothed comb through it, one can see the missing pages and shoddy scans, hinting at the numerous interruptions and interferences it must have gone through. The long delay in releasing the report further complicated matters as many victims and witnesses had already expressed their reluctance to pursue the cases. Statements recorded nearly five to six years ago could no longer be treated as ‘information’ under Section 173 of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023, especially when those who initially spoke out had since chosen not to reaffirm their testimonies.

The Indian film industry has always been under the scrutiny for its failure to be an accommodating working space for women; it is not something that the industry is unaware or ignorant of, but rather, these systematic issues are an accepted but unacknowledged reality. In the Shift Conference, 2019 many actors acknowledged that issues are often addressed only after they escalate, rather than being anticipated and prevented. This was affirmed in hindsight when actress Tanushree Dutta, in 2018, reignited a decade old allegation of sexual harassment against veteran actor Nana Patekar, and gave momentum to the Indian #MeToo. Her admission triggered an avalanche of other survivors from the industry speaking up against directors, producers and actors who had, for years and years, wielded their power to suppress these women.

But the long-term responses? By 2010, Dutta’s career was effectively over, ostracized by the industry. Marred by victim blaming, backlash, and, crucially, a lack of institutional accountability. Actor Asrani trivialized the movement, dismissing it as “All rubbish and 90 percent lies, just to sell to magazines and for popularity.” Abhijeet Bhattacharya, denied the allegations with brazen misogyny, sneering that only “fat and ugly” women were speaking out. The implications of such outrageous responses actively shape the discourse around sexual harassment by discrediting survivors and delegitimizing the very idea of seeking justice.

Data and Denial: Why Does POSH Fail?

India’s Prevention of Sexual Harassment Act, 2013 (POSH) was meant to protect women in all workplaces. However, the film industry operates in a grey area where definitions are ambiguous. The POSH Act mandates employer responsibility for safety, but in a transient industry where workers are often engaged on contractual terms, on project to project basis, making it difficult to establish employer liability, when pinpointing a singular employer is challenging. The Cine-Workers and Cinema Theatre Workers Act, 1984 assigns the role of employer singularly to the Producer, but informality and going off script is rampant in the industry. A workplace, and therefore the employers extend beyond a rigid interpretation, they cannot be restricted to the conventional narrow notion of an “office”. This precarious nature of employment creates lack of accountability, unlike corporate environments with structured hierarchies and permanent contracts.

Another glaring issue is the absence of genuine Internal Complaints Committees (ICCs) in production houses. Despite a clear mandate, too many companies either forgo establishing these committees or set up sham bodies that lack true independence. Out of hundreds, only seven major Bollywood production houses confirmed having anti-sexual harassment cells. Some directors and producers conveniently claim they lack the authority to set up ICCs or implement preventive measures, arguing that they don’t qualify as “employers”. This is nothing short of a blatant misrepresentation of the Section 2(o)(ii) of the POSH Act, which explicitly encapsulates every production unit of a film industry within its scope.

POSH’s failure is evident in the numbers: NCRB data shows workplace sexual harassment cases against women rose from 402 in 2018 to 422 in 2022. This is especially troubling given that women actually under-report crimes against them owing to fear of retaliation, lack of awareness, and societal prejudices.

What’s worse is, over those who do assert themselves, the specter of retaliation looms large. Hiring in Bollywood is largely driven by informal networks rather than formal recruitment processes, and women who dare to report harassment find themselves isolated and blacklisted. Victims remain silent due to the risk of losing their careers and the inevitability of being identified the moment they describe the film set. The fear extends beyond self-victims worrying about their families facing intimidation and harm. Cyber harassment further amplifies this ordeal, with online smear campaigns, threats, and doxxing adding another layer of terror.

The entire inefficacy, however, is founded in the ingrained cultural normalization of harassment. The “casting couch” phenomenon has long been an open secret in Bollywood, often trivialized or even justified as an industry norm. This lets perpetrators operate with impunity, and victims are expected to conform rather than resist.

Recommendations for Industry-Wide Accountability and Reform

POSH implementation at the grassroots level must go beyond mere legal compliance. Systemic reform must begin with the setting up of ICs by production houses, ensuring every category of worker — full-time, part-time, or contractual — knows the whats, whens, and hows of reporting sexual harassment. These committees should not exist simply as tokens like the Association of Malayalam Movie Artists (AMMA) but must be empowered to act without fear or favor. If an ICC under the POSH Act is formed, its members and president will be insiders appointed by the employer– in this case the producer. But in an industry where a powerful few dictate the rules, like a mafia syndicate, producers can be coerced, threatened, or bribed; turning the ICC into a tool for silencing victims rather than delivering justice. The industry has shielded its perpetrators for too long under the guise of artistic brilliance and legacy; it is time to dismantle this carte blanche approach.

Having said that, the responsibility does not rest solely on individual production houses. Film bodies and unions must set clear guidelines on sexual harassment and actively intervene in disputes. Human dignity should be valued as much as financial or creative concerns and inaction only perpetuates the status quo. A coordinated effort between different industry panels is essential, ensuring that no survivor is left in limbo simply because their harasser belongs to a different professional guild.

The industry needs to confront casual discrimination locker-room attitudes, benevolent sexism, and biased hiring. It need not be reiterated that representation matters; women must not only be seen in leadership positions but must also have the right to contest elections within film bodies without intimidation or systemic obstruction. Visible participation in writers’ rooms, script reviews for gender sensitivity, and open discussions on objectification are crucial to dismantling deep-rooted biases. Structural protections alone won’t suffice if exploitative hiring remains unchecked. Mandatory contracts, workplace safety, and basic worker rights secure travel, sanitation, and childcare are essential, especially for women. Failure to meet these basic standards is not mere oversight; it is a calculated neglect of workers’ rights.

The time for passive pledges has long passed. Bollywood must choose: to reform or remain complicit in abuse. Every production that refuses to implement POSH guidelines, every industry body that stays silent in the face of harassment, and every member who fails to push for gender equity is complicit. Every ignored complaint writes another woman out of the cinema’s story. Change is neither convenient nor comfortable but it is the need. The only question now is whether the industry will embrace it willingly or be forced into accountability through sustained public reckoning.

Leave a comment