Introduction

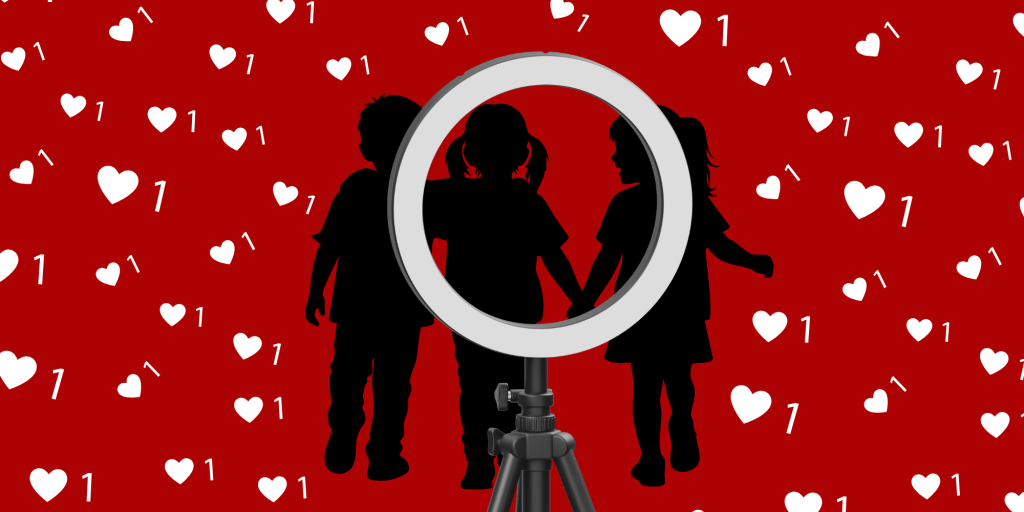

It is now easier than ever to become famous online because of social media influencers and personal brands. Although children under 13 are not permitted to have their profiles on social media sites like Instagram and YouTube, some parents assist by managing their children’s pages in the hopes of assisting them in their pursuit of careers as actresses, models, or influencers. But what happens if the parent starts sharing their child’s life with millions of people on social media? What if they began using their child in material to increase interaction and draw in sponsors? And what if parents know that videos of their children are being saved by hundreds of strangers? How can a child have any control over their online persona when their parents are posting? These worries will only increase as more kids use social media, posing important queries regarding their rights to privacy, even when their parents are the ones sharing their lives, as well as their rights over the content they produce or appear in.

Thus, this essay aims to analyse the legal consequences of such parental behaviour in the digital age, focusing on issues of child privacy and the legal protections available to them. It will also include a cross-jurisdictional analysis to compare global approaches to this issue and conclude with a few suggestions through which child rights can be protected in India’s digital age.

Children, social media, and privacy

With the advent of cheap internet in India, social media platforms have reached all sections of society, and children have become heavily involved not just as consumers, but as creators of content. These “kidfluencers” are often featured in videos doing outdoor adventures, getting ready, or playing with their friends. Such content has become immensely popular with millions of subscribers, exposing them to even more viewers across the world. While this visibility can lead to financial opportunities, with platforms like YouTube paying ₹50 to ₹200 for every 1,000 views, most kidfluencers do not earn a large sum of money. Only the top child creators receive millions of views and, in turn, large sums for their age. It is because of this exposure that they frequently attract the interest of businesses who are eager to collaborate on product promotion.

Most kids do not completely comprehend the ramifications of disclosing personal information online which makes them susceptible to abuse, cyber threats, and even possible manipulation by companies looking to gain an advantage. The problem is made worse by the absence of strong legislative protections, so it’s critical to strike a balance between digital opportunity, privacy and kid safety.

Current Legal Landscape

The principle that the autonomy of a person is inalienably linked to their autonomy over their data is now more or less crystallized after the recognition of the Right to Privacy as a fundamental right in the landmark judgement of Justice K. S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India. However, other than safeguards against the collecting of children’s data, primarily from Rule 10 of the Draft Digital Personal Data Protection Rules 2025, which mandates Verifiable Parental Consent (VPC) for a minor’s data, there isn’t much about a child’s privacy on the internet.

Further, India also lacks laws that prevent parents from using all the money earned by their children which further incentivises parents to keep sharing more and more of their child’s life on social media and earn money. These concerns are not insincere solicitude. In the recent past, we have seen the constant online harassment of ten-year-old Abhinav Arora, who calls himself a “spiritual orator”. This has prompted us to have a more comprehensive discussion about the role of parental responsibility and children’s privacy in the creation of such content.

If we look at Section 3 of the Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, 1986 and guidelines of NCPCR, both permit a child to work in “family enterprises” as “any work, profession, manufacture or business which is performed by the members of the family with the engagement of other persons.” However, there are no legal provisions as regards parents operating accounts, where the child is alone responsible for content creation.

Another point of concern is the absence of children’s right to be forgotten when they become adults. This gap means that once a child’s content is uploaded, often by their parents they may have limited legal recourse to remove it when they grow older.

In light of these gaps, it is evident that India’s legal framework remains insufficient to safeguard children’s digital autonomy and financial rights in the era of social media. While existing regulations focus on data protection, they fail to address the broader implications of parental control over a child’s online presence. The absence of clear legal provisions allows unchecked exploitation, leaving children vulnerable to both privacy violations and financial misuse.

Cross Jurisdictional Analysis and International Legal Frameworks

In France, the law protects the revenue of child influencers. In particular, only a portion of the child’s earnings are given to the parents; the remainder is deposited in a special savings account that the youngster will have access to upon reaching adulthood or legal adulthood. The new law also makes it clear that children can exercise their right to be forgotten even without the parent’s permission. Additionally, this regulation covers child influencers, such as child performers or models, under the French Labour Code. According to the law, parents must obtain permission from the government before their children can engage in labour-intensive internet activities. By protecting their profits, guaranteeing financial security, and prohibiting parental exploitation, a similar rule should be implemented in India, offering vital protections for child influencers. The establishment of explicit criteria for child influencer’s working conditions, protection of their well-being, and restriction of excessive digital exposure would result from their recognition under labour laws. The right to be forgotten would also enable kids to take back control of their online persona as they became older. In the digital age, such a legal framework would balance safeguarding children’s rights with encouraging creativity.

In the US state of California, Coogan Law protects child actors by preventing parents from using money earned by the child. This law mandates the creation of a trust account that can be monitored by the legal guardian, but not withdrawn from, until the child attains legal age, at which point the child can withdraw that money. Implementing a similar legal framework in India would serve as a safeguard against the potential exploitation of child content creators by mitigating the financial incentives associated with excessive parental involvement in their online presence. By reducing the commercial motivation for exposing children to social media at a young age, such a law could also contribute to better privacy protection for minors.

Conclusion and Suggestions

From the above discussion, it is apparent that there are various concerns regarding children and their role as content creators with lack of even basic laws for their protection. The current legal framework falls short of protecting the broader rights of child content creators. In the absence of explicit regulations governing parental control, financial earnings, and digital autonomy – minors remain vulnerable to exploitation and long-term privacy violations. The international examples from France and the USA underscore the importance of a holistic approach that not only safeguards a child’s immediate privacy but also secures their future autonomy and financial interests.

To protect such child creators, an amendment should be made to the Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, 1986 differentiating the work of child creators from “family run enterprises” and a trust should be created in their name where money earned by them can be set aside, which they can claim after attaining the age of majority. Further, a provision should be added which prevents parents from spending money earned by their children for their personal benefits. Additionally, Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 should be amended to incorporate an unequivocal right to be forgotten for minor creators, thereby empowering them to request the removal of any content posted by their parents upon reaching adulthood, without exception.

In the end, we conclude by saying that ensuring robust legal safeguards for child content creators is essential to secure their future and well-being. Collective action from lawmakers, industry stakeholders, and society is imperative to create a safe and equitable digital environment for all children.

Leave a comment